Late in 2014, Kate Greder from ISU Museums approached me to help curate an upcoming exhibit of Chuck Ginnever’s Rashomon sculptures. “Curate” - I had to look up what this might mean. And read a lot more about Ginnever’s work. But I said, “Sure!”

The exhibit was placed over Christmas, so early in the new year a few members of our ISU graphics working group (GG), ventured over to the courtyard of the Food Sciences Building to take a look. The first views were of them buried in snow:

The exhibit features 15 identical units, each capable of assuming 15 distinctly separate and stable positions. It is inspired by the seminal Japanese film “Rashomon” in which one story is told from multiple perspectives. The difficult part for the museum staff was the configuration, to be sure that the display satisfied the constraint that all pieces were oriented uniquely. To ensure this they had the exhibit shipped with the configurations marked so that they could be confident that the placements were unique.

When the snow cleared we got into the courtyard to take a closer look (Xiaoyue Cheng, Alex Shum, Eric Hare, Heike Hofmann and myself):

It was hard to see that they actually were all the same shape. The lengths and widths of parts of the sculpture conflicts with 3D perspective, playing with the perception of the shapes. We explored the sculptures from many different angles, and walked among them. The nice part of the space is that the units were very close to each other. Then we noticed that some sculptures were in identical placements, 3 pairs to be specific. Of the the 15 units there were only 12 different positions used. This had to be fixed. But even the Ginnever web site only provides 10 unique positions.

This is a story of statistics and art.

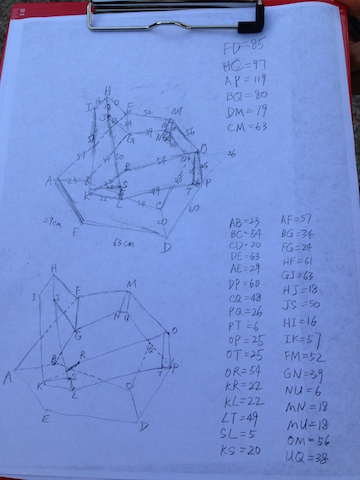

Our first step was to label the vertices, and measure the distance between each vertex:

At first we thought we could manage with just the main vertices measured, but within a few weeks it was clear that we needed to go and measure the distance between each pair of vertices.

The second step was to virtually reconstruct the sculpture, using multi-dimensional scaling (MDS), at least we hoped this might work. Given an nxn distance matrix, MDS will provide a layout in k-D which best matches the distances. For our purposes k=3, we need a 3D layout of the vertices that matches the distance matrix provided, and hope that this layout matches the sculpture shape. This ended up being an iterative process, because MDS almost worked, except small wrinkles, like a pair of vertices flipped, or a side twisted. So we would go back to the sculptures and re-measure the distance, find we’d messed it up (slightly), then re-do MDS. (R code is here.) The end result is very close:

From the virtual model, and then experimenting with the actual unit, we found 15 unique positions. These positions are labelled by the vertices or edges that touch the ground.

And this led to producing a catalog of the 15 unique positions for the units.

In addition, we weekly went to eh exhibit and rotated two units, essentially swapping the orientation, with the purpose to make a video at the end of the 5 month exhibit where pieces appeared to be rolling. It wasn’t as successful as we had imagined, because the light conditions, and green content of the courtyard changed so much. We did a one time series of photos instead and turned these into a short video:

Rashomon from Di Cook on Vimeo.

The exercise was completed with the help of many members of ISU GG, but most intensively with Xiaoyue Cheng and Heike Hofmann, and museum staffer Kate Greder. Here are a few more photos taken during the exhibit.